Week 9 Changing Names

When I first worked as a genealogy librarian, people would often comment that their family names were changed by the government, like census workers, or upon arrival at ports like Ellis Island. This was one if not the most common myth among amateur genealogists. Then I attended a lecture by an archivist from the National Archives where she laid that myth to rest, shredding the myth to pieces, actually. If you want to read more, the NYPL has a great blog entry on the topic, it is well worth reading: https://www.nypl.org/blog/2013/07/02/name-changes-ellis-island

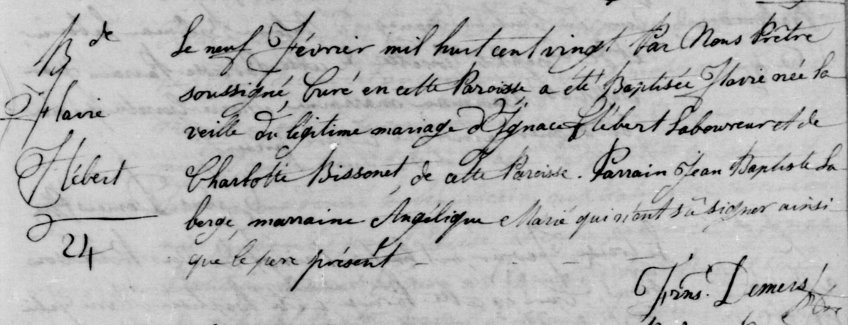

With all that well known, I have no end of ancestors with name changes. At best they are baffling, at worst and all too frequently they cause all sorts of challenges to the researcher. I have a 3rd great grandmother whose birth name was probably HEBERT. She was born and baptized in Quebec in 1820 and when you say the surname aloud, like a French speaking person might, you hear the word “abare” – imagine the potential spelling variations for that name.

There were many reasons for name changes, probably the most common was when women married. The loss of women’s identity after marriage is another constant challenge to genealogists. Is there anything more infuriating than an obituary that lists a surviving spouse as “his wife” or lists the decedent as “Mrs. John Smith”?

There were societal reasons for name changes, my SAMMONS’ ancestors first lived in the New Netherlands with the surname THOMASZEN which was no doubt a patronymic – that’s another whole blog post. All I found noted about this name change was that the second generation of the family changed the name to SAMMANS. 1 (In this paragraph alone, you have 3 variations of the same surname!) Did the Dutch family change the name to Anglicize it? We will probably never know.

The best advice I can give to researchers is to let go of your notions of “correct” spelling. When my French great grandmother said her name to an English only speaking American it sounded like ABARE not HEBERT. It’s likely she was not literate and even if someone asked her to spell it, she might not have been able. And this was a pervasive problem. She married a man named LaFORCE. His name in her widow’s Civil War pension application was recorded as LaVORCE.

A good researcher must search for all variations, always keeping track of the potential spellings of a name and the changes in the names. Not doing so presents the risk of not finding our ancestors or confusing them.

- Edwin R. Purple, Contributions to the History of Ancient Families of New Amsterdam and New York (privately printed, 1881) 25. ↩︎